I am lucky enough to have been invited to the 2015 Palestinian Festival of Literature. Here is a despatch from days one, two, and three.

Lego State

Israel happens so suddenly.

There we were one moment on the coach in Amman. Our tour guide, Ruby, started talking about crossing the border into the West Bank at exactly the same moment as the coach suddenly started reversing, a possibly inauspicious sign. Then we sped through Amman and its pleasant emptiness into the Jordanian countryside as Ruby gave us an introduction to the country that lasted about five minutes. “Jordan is the ‘safety bulb’ of the region”, she declared. It is the only Arab country that has peace with Israel other than Egypt.

“When people visit Jordan for eight long days what do they do?” she asked cryptically. Ahdaf Soueif, equally cryptically, described us as “moving down vertically” from Amman to the King Hussein Bridge and then immediately abandoned all descriptions of geography.

Ruby pointed at distant inconsequential green things and mentioned that they were the site of amazing biblical happenings, happenings of huge moment that would produce new physical realities all these thousands of years later; the River Jordan, pumped dry, and the bridge above it, reluctantly patching together the two entities on either side, a conduit for all that sadness of terminated returns, and about turns.

Over we went and joined a queue of coaches. We stopped alongside a watchtower covered in the cobweb of camouflage netting. Two armed soldiers–who looked about ninteen years old– stood having a laugh, elbows resting on the railing.

And then, suddenly, virtually all the Arabic disappeared, replaced by Hebrew and its spikiness. We got off the coach and fought our way into the scrummage.

So chaotic, so hot, so hellish, so reliant on pushing and angled elbows shoved in obstructive ribs was this checkpoint that Sinan Antoun and I both wondered out loud at the same moment: had we got things wrong, is this checkpoint in fact under Palestinian control? Did not the Zionist state after all make the desert bloom? And is it not an island of calm and order in the sea of barbarian anarchy that surrounds it? What then is this almighty hell?

This is how it works:

First, you dispense with your luggage at a counter via a functionary who will barely look at you and who processes your bag and sends it on its way on the belt into the arrivals hall directly behind him.

Next, you queue up again, alongside many others: Chinese Christian pilgrims; a solitary nun in her holy starched white; huge tourist groups from Malaysia wearing matching blue bags; and Palestinians carrying their blue travel documents. In what seemed to be a concession to our discomfort, the authorities have thoughtfully erected a large roaring industrial fan. It belches out air and water droplets, but also blows cigarette smoke in everyone’s faces as well as raising the noise levels.

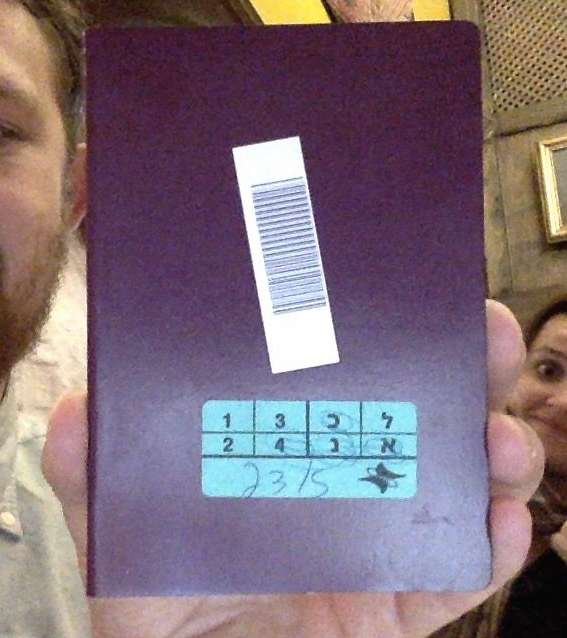

When you eventually reach the counter you are met by a young woman or man who smiles in your face and asks you how you are and then reads the name in your passport and says, “Sarah?” or whatever your name might be. If you were born somewhere unsavoury she or he will ask you about that. And she or he will put a green sticker on the back of your passport with "1-4" written in English and four characters in Hebrew. Like this:

Then you go into the actual border crossing building, and must queue up again. Here you compare stickers and try and guess why some of you have numbers circled on it and others do not. “Danger squiggles,” Rob Stothard called them. He was born in Bahrain and the sticker official had commented on this. Ismail Richard Hamilton had the same; born in Saudi Arabia. The x-ray machines meanwhile were manned by yet more pubescents, one of them in a t-shirt emblazoned with "HOLLYWOOD." Here there was another mad scramble for the trays in which bags are placed on the x-ray belt.

Having gone through this stage, you are at the final hurdle and enter a large hall where you see yet more ginormous queues and your heart drops. Two irascible women manned the counters where we queued up, variously talking to each other in Hebrew and barking at travellers in heavily-accented Arabic. At one point, a verbal altercation broke out among passengers and one of the women stood up and clicked her fingers and made some vague sounds of approbation reminiscent of a teacher dealing with difficult children.

At this counter the real questions begin. I got:

- what is your mother’s name?

- what is your father’s name?

- what is your father’s father’s name (twice)?

- where do you live?

- what is your job?

- how long did you stay in Lebanon?

- why did you go to Lebanon (twice)?

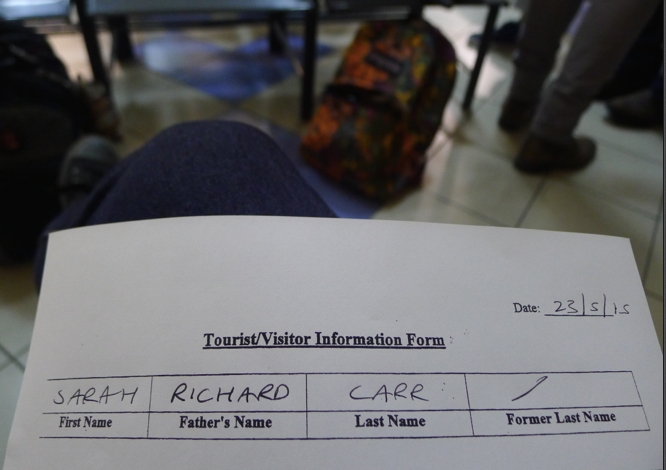

Having established that my father’s name is Richard, and his father’s name was Edmund, the counter lady then made a phone call, maybe to the dangerous Christian names hotline, and then handed me a badly printed out form. She instructed me to piss off and fill it out. “Somebody will come and get you,” she said. Of note here is that they did not ask me whether I have any other nationality which surely would have been the fast track route to establish my potential persona non grata credentials rather than climbing up and down my family tree.

Lucky git and also priest Giles Fraser meanwhile sped through by virtue of busting out some basic conversational Hebrew and hung around outside eating falafels while we endured inside.

I joined the other Palfest participants lingering in this purgatory. Here, the routine is that you fill out the crappy form while waiting for someone to call your name. And then you are asked more questions about your basic information–usually ones you have only just been asked–and so the effect is like when you sign up for a website and fill out all the boxes and then the net crashes and you have to fill it all out again. Its like a sort of human Zionist Amazon My Account page. Then you are asked to sit down, and a little while later someone else calls your name again and (if you are lucky) hands you your passport and off you go. By the time I joined the others, people were trickling out one by one and these jokesters were already going on about people being voted off the island.

My name was called after an interminable amount of time by a short woman/girl who truly looked about eighteen years old. With each layer of interrogation, the rule seems to be that the official gets younger. If they keep you overnight for questioning you are probably cross-examined by a toddler. Anyway, this young woman took me aside and asked me the same questions about my father’s father’s name (still Edmund) but this time she mixed it up with what is your mother’s father’s name which unfortunately for me is Aref Ibrahim and which no matter how Croydon you try to pronounce it is inescapably Arab. Having established that my mother was born in Cairo she then pursued a line of questioning that revolved around trying to establish that I am from Hamas.

- do you ever go to Gaza?

- do you ever go to Rafah?

- do you have family in Gaza?

- etc

I decided to cut to the chase and informed her that I am not of Palestinian origins if that is what she is getting at, prompting her to respond with: “Yeah OK but you know borders change a lot round here, ha ha ha.” I was so gobsmacked I could not reply, but she had finished with me anyway so I trundled off and sat back down. Sinan meanwhile, when they discovered he was of Iraqi origin, was asked “and how are things in Iraq?” The only conclusion to be drawn from all this is that they are taking the piss.

Our time waiting was brightened up considerably by two revelations by Daniel Hilton:

- He once lost his passport in Belize, and the temporary passport he got to replace it could not accommodate all his names so they just shortened one of his middle names and dispensed with his actual surname and now all his official documents list his surname as WILLI.

- His hair is so very long in his very old passport photo that when he went to Syria the gentleman at passport control said to him, “But this is not you. This is a woman.” Behold:

Nearly six hours after we reached the checkpoint, a uniformed soldier called my name and this exchange took place:

Soldier: How are you?

Me: Fine

Soldier: Are you well?

Me: Yes

Soldier: I have some bad news and some good news.

Pause

Me: Oh

Pause

Soldier: You want the bad news or the good news first?

Me: Ha ha, the bad news

Soldier: [As he handed me my passport with the paperwork indicating I had been allowed entry] Enjoy

Me: Thank you [tosser]

Was this some supremely arch, dark commentary on Israeli society? Or was it just a dickhead toying with someone he knows is powerless.

I cannot begin to imagine how it must feel to be Palestinian to have to endure that kind of treatment, that humiliation, at the hands of an occupier in order to enter your own country. One of the Palfest participants whose father is a 1948 refugee said that he was able to visit Palestine in 1997 and that she has never seen the kind of pain etched on his face as she saw in pictures of him there. He felt that Palestine belonged to the Israelis by then, that they put down roots too deep to dig up.

And they are still putting down those roots. When you leave the crossing, two of the first things you really notice are illegal settlements sitting on top of the hills of the West Bank like mushrooms in a field at varying stages of maturity, and the separation wall which separates not Israel from the occupied West Bank but the occupied West Bank from the occupied West Bank. There is a brutal absurdity to it all, these Wizard of Oz-type settlements (some are the size, and have the permanence, of a small town) gleaming in the distance, the Bedouins and their animals living in squalor below, the kaleidoscope of the number plates and the roads they will and will not allow you to travel down according to what colour it is and all of this glued together by the military, present everywhere you look.

There is a piece of graffiti near our hotel that I really like and which says: dawlat al-lego, lego state.

Nothing built is immutable, everything can be taken apart.

What is Your Occupation?

On Sunday, the improbably-named Ray Dolphin gave us a crash course on the occupation at the headquarters of the United Nations Office for Humanitarian Affairs for the Occupied Palestinian Territories. The headquarters is a beautiful old building with a verdant garden in which there is a pagoda well-manicured borders. It is where Moshe Dayan and his Jordanian counterpart drew out the Green Line, so called because they used a green pen. Ray says that the table they used to do this was not level, causing inaccuracies of inches on the map which translated into kilometres in reality.

Ray bombarded us with a litany of depressing facts. He told us that almost a year after Israel destroyed twelve thousand homes in Gaza during its war on the strip, there has been almost no reconstruction. Some families have simply returned to the ruins of their homes and pitched tents. In October 2014, countries loudly pledged millions for the reconstruction of Gaza during a donor conference in Cairo. Not much of it seems to have translated into anything of substance. And in any case, even if it did Israel has not let construction materials into the strip since 2007 because, it says, Hamas would use it to build bunkers. The tunnels between Egypt and Gaza on which the latter’s economy depended are now all closed, as is the crossing between the two countries thanks to a certain busy ex-field marshall and his combover.

The occupied West Bank meanwhile houses 556,000 settlers (twenty percent of the Palestinian population), 150 settlements and one hundred outposts. The difference between a settlement and an outpost is that a settlement is authorized by the Israeli government while an outpost is not, but the government is perhaps too busy to object with any force because it is preoccupied with furnishing said “illegal” outpost with roads, water, and electricity supplies.

Almost forty-three percent of land in the West Bank is controlled by settlements. In 2014, there were 221 cases of settlers damaging Palestinian property and 110 cases of incidents involving settler violence that resulted in physical injury to Palestinian victims. There does of course exist a legal mechanism allowing Palestinians to report such crimes, but who are you kidding. The result is that settlers routinely intimidate Palestinians and take over their land with virtual impunity.

The wall meanwhile continues to snake its way through the West Bank. It will be 700 kilometres long upon completion. Flipping through a powerpoint showing diagrams illustrating the various, cumulative, physical insults inflicted on the West Bank since 1967, Ray said the wall’s main effect will be on agriculture.

Are your eyes beginning to glaze over? Offences against agricultural are not very sexy, after all. But consider the example of the village of Jayyus that Ray told us about.

Most of Jayyus’ land and water wells are on the other side of the wall from the village. This means that farmers need a special permit to access their land as the area has been deemed a military zone. Many applications by farmers are refused for security reasons. Farmers must also prove a connection to the land, something to show that they own it. This is a problem because most of the West Bank has not been formally surveyed (surveying started under the British Mandate and continued under Jordanian rule but Israel suspended it all in 1967). In addition you also have to have a minimum amount of land. The result of all this is that less than half of West Bank farmers obtain permits to access their own land.

If you are a farmer that does obtain a permit, you must engage in a farce in order to tend to your land.

You wait at one of the electronic gates controlled by the military until army soldiers show up. You are let through and locked in until midday when the gate is again opened. In the early evening, the army returns and closes the gate for the final time that day. Farmers are not allowed to stay overnight on their land, meaning that you have a maximum of ten hours each day to cultivate it. Also, you cannot irrigate your crops in the evening when it makes most sense to do so. Satellite imagery shows that lots of land has been abandoned. Wheat is often grown instead of other crops, because it needs less attention. But it makes farmers less money.

Note also that of these eighty-five electronic gates, only nine open on a daily basis. The majority of them only open during the six weeks of the olive harvest in October of each year.

Some other facts about the West Bank:

- Eighteen percent of the occupied West Bank is a military area. Palestinians are not allowed to enter these areas without permission.

- Ten percent of the occupied West Bank is a nature reserve. Palestinians are not allowed to cultivate these areas or graze animals there.

- Sixty percent of the occupied West Bank is controlled by Israel, which means that virtually every aspect of a Palestinian’s life is mapped out by Israeli diktat.

- Between January and November 2014 only one application by a Palestinian to construct something on territory in the West Bank controlled by Israel was approved. One. You will recall that there are a combined total of 250 illegal settlements and outposts whose inhabitants build and construct freely.

Things get truly mental in East Jerusalem, which is governed by its own nightmarish legal framework.

Palestinians in East Jerusalem do not have Israeli citizenship. They have permanent residence. What this means is a separate, blue, ID card which allows Palestinians to live inside Israel and Jerusalem, but not inside the West Bank. Live abroad as a blue card holder for more than seven years, or acquire citizenship from another country, and you automatically lose your residency. This has obvious implications for marriage, and for the children of unions between Palestinians from the West Bank and East Jerusalem because Palestinians from the West Bank need a special permit to enter East Jerusalem (incidentally, if you obtain such a permit you cannot enter East Jerusalem with your car). The result is that there are four thousand unregistered children in East Jerusalem who cannot go to municipal schools.

All this can seem a bit remote when you just read it. But to occupy is to possess, to fill up space or time with a presence, to dwell inside something, to contain it from within and without. There is a brutal physicality about it. In Egypt when Cairo’s authorities wanted to shut down protesters they built giant, disfiguring walls of huge blocks in the centre of the capital that reshaped the way that traffic moves and blocked the city’s arteries. The walls were an aberration, monuments to the regime’s failure to control the people through popular approval, through dialogue, and an admission that it has no interest in winning this approval.

It is the same story in Israel. At the Qalandia Checkpoint Palestinians from occupied Ramallah wishing to enter occupied East Jerusalem queue up for hours underneath hulking watchtowers surrounded by shit and burnt rubbish and resolute graffiti and go through a turnstile reminiscent of the machinery used to control cattle during the process of inoculating them.

When we went through there were two young female soldiers manning the checkpoint, which was empty. One was lying on her flak jacket on the floor, apparently asleep until she jumped up to look at the x-ray machine monitor. Another was chatting on Whatsapp. People crossing the checkpoint must hold their document up to the glass for inspection. If the soldier requires a closer look the traveller must put the document through a tiny slit in the counter.

I struggled to put my passport through so narrow and cumbersome is this slit and was once again struck by how separated we were, the soldier and me, despite our physical proximity. Which is the point. When dealing with Palestinians Israel puts the gloves on in every sense of the word.

Ray took us to Sheikh Jarrah, an area of East Jerusalem. The street is home to Palestinian refugees who fled Haifa in 1948 and were re-homed here by UNWRA in 1956. The Council of Sephardic Jewry claims right to the area on the basis of an ancient Ottoman document. In August 2009 the Israeli police evicted the residents of two homes and literally threw them into the street. Within half an hour settlers had moved in to the houses. In the el-Kurd home on the same street a Palestinian family lives at the back of the house while settlers have occupied an extension built on the front of the house which a court has deemed illegal. You can watch the very distressing video of the men taking over the extension here.

On the day we were there the street was quiet. An elderly man drew up in his car, parked it, took his shopping out, unlocked his front gate, went inside. A girl played in the street. And then there were the houses occupied by settlers. That sudden violence again, the street’s symmetry interrupted by their chaos; makeshift structures erected on the balcony covered in bits of fabric and cardboard, a sofa cushion strewn on some unidentifiable makeshift structure, the visual assault of the graffiti, the jumble of it all. And above all, that separation, that deliberately pronounced other-ness, the knife in the fork compartment.

In Hebron the excellent Sami from the Hebron Rehabilitation Committee commented that Israel likes to dominate with its architecture. You will have probably heard of Hebron, the West Bank city where the settlers throw shit out of their windows at Palestinians and Palestinians have to use ladders to enter their homes through windows rather than the front door because the Israeli army has sealed it shut.

In Arabic Hebron is called al-Khalil, which means bosom friend. It is so named because of its association with Abraham, who was known as khalil al-rahman, or beloved of God.

Khelwa, which comes from the same root as al-Khalil, means to spend time with a dear friend. The nomenclature has a dark irony, because Hebron sums up the occupation, of two peoples in close proximity who are linked by mutual contempt rather than love. In 1968 Rabbi Moshe Levinger and a group of Israelis pretended to be Swiss tourists in order to rent rooms in a main hotel in Hebron. They then refused to leave. They were moved to what would eventually become the settlement of Kiryat Arba in east Hebron. Since then four other settlements have been established, one in the building that formerly housed a Palestinian boys school. The settlements have sucked the life out of Hebron’s old city; there are 1829 shops in the area and only two hundred are open.

The settlers are obviously motivated by the idea that they are resurrecting a Jewish claim to the city, and as usual the Israeli state supports them in this project. two thousand soldiers protect four hundred settlers living among forty thousand Palestinians. Walk through the old city and you will encounter machine-gun carrying soldiers on patrol in the market’s not very busy alleyways. Above your heads in one street are Israeli flags and the netting that stops the rubbish that settlers throw out their windows from landing on people’s heads. The Beit Romano settlement, the one built over the school, is a monstrous, imposing presence that towers over the streets below. It looks like a government building, with its army watchtower.

The establishment of a settlement in Hebron means the demise of anything immediately near it, like gangrene spreading to surrounding cells. Rooms are deserted, windows boarded up. In addition to the permanent edifices, makeshift barriers of coiled barbed wire and bits of detritus stud entrances to streets leading to settlements. And then there is the gold market, entirely shut down by military order in 2000. Shop owners were not given any warning before the closure and had to leave behind their wares, which were subsequently looted. Since the street is directly under a watchtower Sami suggested that the only conclusion that can be drawn from this is that it happened under the army’s eyes and was certainly not carried out by Palestinians.

The occupation goes full throttle on Shuhada Street. This is accessed via a security checkpoint overlooked by a watchtower. The shops on this street are all empty; it is a ghost town. Palestinians are allowed to walk for about 800 metres on this street before they must turn right off it or risk arrest or worse, because this is where the settlement starts. Once, in another part of the town with a similar restrictive policy, a six-year-old Palestinian boy carrying a box was shot dead for failing to stop when a soldier shouted at him to do so. The problem was that he was deaf.

At the end of Shohoda Street, underneath the Ibrahimi Mosque which sits on an elevation above it there is a Jewish guest shop (also a settlement) that sells religious trinkets whose WiFi Sami told us was once “kill the Arabs”. They have changed that now and the authorities have also allowed a couple of Palestinian-run souvenir shops to open opposite it, Sami says because a deserted tourist site gave tourists the wrong impression. Beyond the shops there is a small, well-cared for green with picnic benches and leafy trees under which a large group of soldiers reclined. Rob Stothard photographed a soldier praying at a picnic bench, the soldier gave him dirty looks. Jewish tourists, the women all with their heads covered staggered through the merciless heat towards the synagogue. One middle aged woman waved at the soldiers under the tree, uttered some words in Hebrew enthusiastically. The soldiers waved back languidly.

There is nothing else on this street now, just the settlers, the eerie shuttered shops and a few Palestinian families who have held out and refused to leave despite the fact that they are forced to access their homes using ladders. The place is reminiscent of a disused film set in its silence and stillness, an effect compounded by the stories settlers have spun in the from of posters describing Hebron’s distinctive Jewish character and history (to the exclusion of anything else). There is the usual shrillness about it all, the repeated mentioning of the Arabs and their terror and the turning inside out of the truth that is so characteristic of (and infuriating about) hasbara. Here’s an example of that.

The lies and propaganda are a part of the occupation’s architecture as much as the concrete and barbed wire, since not everyone can be contained in a tiny bit of land and physically controlled.

Leave the West Bank and enter Israel and there are no more army watchtowers, no more checkpoints, no more walls. You are surrounded by well laid out motorways and tasteful homes on top of spectacular rolling hills. In Haifa the sea laps at the shore while people enjoy drinks in pavement cafes overlooked by the spectacular Bahai Gardens. Here, on first impression, the occupation ceases to exist and Gaza is on another planet. This oasis of pleasantness, where women can wear what they want and people can love who they want and live in nice homes and have access to good healthcare and beautiful beaches. But all of this is built on names wiped off the map, on memories of villages destroyed and people killed and who are still being killed, on families swept around the globe like leaves on the wind, who are forced to put on the coat of another nationality but will never be entirely comfortable in it, who if they do not acquire another nationality live a precarious existence spent between airport detention rooms and police stations and refugee camps while a stranger enjoys a breeze on the seafront of Haifa without giving it a second thought.

Occupation fills space and time beyond walls and borders, beyond the farmer waiting for the military gate to open, beyond the worker who spends hours at the Qalandia checkpoint, beyond the schoolboy in Hebron arrested because he has dirty hands and therefore might have been throwing stones. To swallow Israeli propaganda about the endless terror and the homemade rockets justifying a bottomless pit of hell is to allow the occupation’s brutality to endure. To fail to challenge the Israeli state’s narrative while three hours away from you people live under military law and are humiliated, detained and worse is to allow the’s occupation’s brutality to endure.

[These dispatches were originally published on inanities.org]